Researchers at the Mayo Clinic published a study in 2019, showing that a convolutional neural network (CNN) enabled artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm could accurately predict the presence of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) from an electrocardiogram (ECG) taken in sinus rhythm (SR). The study was groundbreaking in the sense that even expertly trained electrophysiologists are not capable of reliably making this determination. It’s extremely important because AF increases your risk of stroke by 5-fold (which can be managed with appropriate anticoagulation) and up to 35% of people with AF remain undiagnosed, in-part because we lack proven, cost-effective measures for AF screening and it is not recommended by the USPSTF. However, a more targeted approach, with tools like this, would increase the AF prevalence and positive predictive value (PPV) of screening and would be more likely to produce clinically effective results. Yet a major roadblock, even to groundbreaking results like this, are the need for clinical and external verification prior to their implementation in the real world; luckily both have now been completed (and reviewed below) which brings us closer to putting this cutting edge technology into clinical practice.

Original Study

The original study was published by Attia et al in the Lancet. The novel idea was that an AI algorithm (in this case a CNN) could learn to recognize subtle patterns and features in a SR ECG that are associated with paroxysmal AF and that this model would outperform conventional and manual methods, such as P-wave morphology analysis.

The dataset included >180,000 individuals with >600,000 ECGs spanning a time period from 1993 to 2017. Patients were labeled as having AF if they had at least one documented ECG showing AF or atrial flutter during this time period. Labeling was completed by professionals under the observation of Cardiologists. These ECGs were used in the supervised training, validation and testing of the CNN algorithm for AF detection. The researchers found that a single AI analyzed SR ECG identified AF with an AUROC of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.86–0.88), sensitivity of 79.0% (77.5–80.4), specificity of 79.5% (79.0–79.9), F1 score of 39.2% (38.1–40.3), and overall accuracy of 79.4% (79.0–79.9). Accuracy increased to 83.3% when multiple ECGs for individual patients were used.

External Validation Study

A key limitation to the study discussed above is that it was trained, validated and tested on ECGs which were internal to a single center. All trials and studies are susceptible to bias, uncertainty and error which make validation important, especially AI algorithms that are heavily dependent on their internal training data. External validation is the process of testing the performance and applicability of results on new data that are independent from that used in the original trial. Among other things, external validation helps to:

- Assess the reliability and accuracy of the trial’s methods, outcomes, and conclusions

- Identify sources of heterogeneity, inconsistency, or contradiction

- Evaluate the generalizability and transferability of the trial’s results to different populations, settings, or subgroups

- Support the development and implementation of clinical guidelines and recommendations

Fortunately, an external validation study was recently completed by Gruwez et al on two cohorts in Belgium. First, these researchers recreated the CNN algorithm with ECGs taken from a population of patients at a single center in Genk, Belgium and then validated this CNN on a separate population of patients at another center in Maaseik, Belgium. ECGs from the first center were collected from Oct 1, 2002 through Aug 31, 2021 and at the second center from Oct 17, 2014 through Aug 30, 2021. All ECGs were taken in SR and were standard 10 sec samples taken at a rate of 500 Hz.

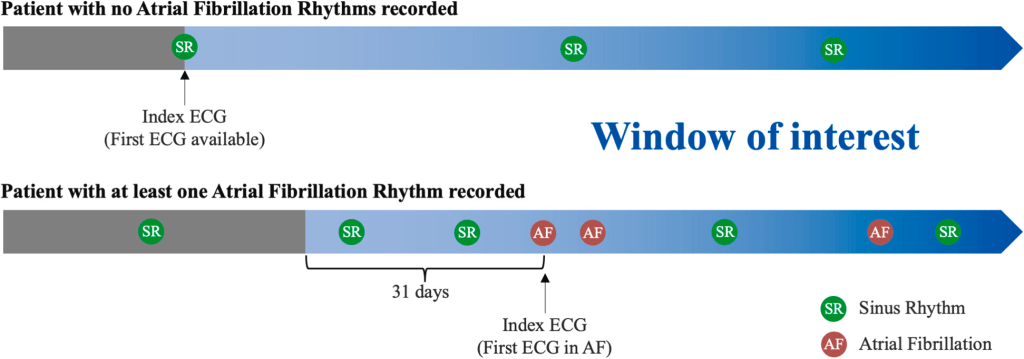

To select ECGs, this study group followed the same outline as the Mayo group. Specifically, for patients without AF, the window of interest started with the first SR ECG in the study period and lasted until the end of the inclusion period. For patients with AF, the window of interest started 31 days prior to the first ECG showing AF or atrial flutter and lasted until the end of the inclusion period (see image below).

For training purposes, all SR ECGs in the window of interest were used for CNN development, but only the first ECG of SR was used for validation, testing and external validation. For evaluation purposes, they included similar measures to the original outcome (namely AUROC, accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, and F1 score) but also included the area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC). The model itself, like most CNNs, gives a probability that a specific SR ECG is taken from an individual that has atrial fibrillation. For assessment purposes, a probability threshold was chosen above which an individual is said to likely have AF or to likely not have AF. That threshold value was derived from the validation dataset to be the level at which accuracy, sensitivity and specificity all have a similar value. Interestingly, to investigate the results of the model in higher and lower prevalence groups, samples of patients with and without AF were left out of the analysis and sensitivity testing was performed.

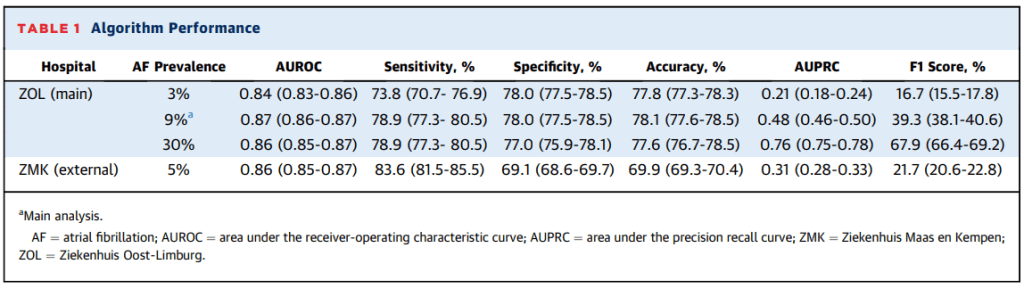

The developmental dataset included >140,000 patients with >490,000 ECGs and the external validation dataset included >26,000 patients with >70,000 ECGs. Results from the developmental analysis found an AUROC of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.86-0.87) for the detection of AF. Further results included an F1 score of 39.3% (38.1-40.6), sensitivity of 78.9% (77.6-78.5), specificity of 78.0% (77.5-78.5), and accuracy of 78.1% (77.6-78.5). The AUPRC was noted to be 0.48 (0.46-0.50). The AF prevalence in this primary analysis was 9% and the threshold for AF detection was set at 78.1%. In secondary analysis of these results, adjusting the prevalence of AF showed very similar AUROC, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity, but changed the AUPRC and F1 scores to 0.21 (0.18-0.24) and 16.7% (15.5-17.8), respectively, for a prevalence of 3%, and 0.76 (0.75-0.78) and 67.9% (66.4-69.2) in a sample prevalence of 30%. Finally, the external analysis resulted in an AUROC of 0.86 (0.85-0.87), AUPRC of 0.31 (0.28-0.33), sensitivity of 83.6% (81.5-85.5), specificity of 69.1% (68.6-69.7), accuracy of 69.9% (69.3-70.4) and F1 score of 21.7% (20.6-22.8). The AF prevalence in the external group was 5%.

Overall the results were quite consistent and very similar to the original Mayo study, but the accuracy and specificity of the external validation cohort (data from outside the center where models were developed) was slightly lower (P<0.05).

Clinical Utility

So now we have reviewed a groundbreaking AI algorithm with the ability to identify paroxysmal AF from a sinus rhythm ECG with high accuracy and we have seen this algorithm recreated at an outside institution and externally validated. This is great, but most importantly, we should next be asking what the clinical utility might be? It might seem obvious why we would want to identify patients with a high likelihood of having AF, but if there is no clinical utility in doing so (i.e. knowing they have AF would not change any meaningful clinical outcomes) then perhaps it is not worth the unnecessary cost to the health system to find out, and it would save patients the anxiety of dealing with a potential AF diagnosis if there would be no change in their management. Luckily, this has also been studied by the Mayo Clinic group that completed the original study discussed above.

Specifically, they retrospectively identified patients in their health system who had a sinus rhythm ECG and were eligible for anticoagulation (via in interesting natural language processing EHR data review), which would theoretically prevent them from having a thromboembolic event, and prospectively enrolled them in a screening trial. The dates of the retrospective review spanned the period from Jan 1, 2017 to Dec 31, 2020. Patients were eligible if they had a SR ECG during that period, were adults (>18 yrs), with a CHA2DS2-VASc score >/= 2 (men) or >/= 3 (women) and did not have a contraindication to anticoagulation or happened to already be taking anticoagulation for other reasons. These patients were divided into quartiles of elevated (top 1%, 1-5%, and 5-10%) risk of AF as well as reduced (bottom 90%) risk based on the AI ECG prediction outcome previously discussed. Patients who were confirmed to be eligible and agreed to enroll in the trial were sent a continuous rhythm monitor (MoMe 3-lead monitor) that they wore for up to 30 days. The outcome of interest was AF lasting 30s or more as identified on the monitoring device. Secondary outcomes included other AF duration thresholds and total AF burden as well as other arrhythmias.

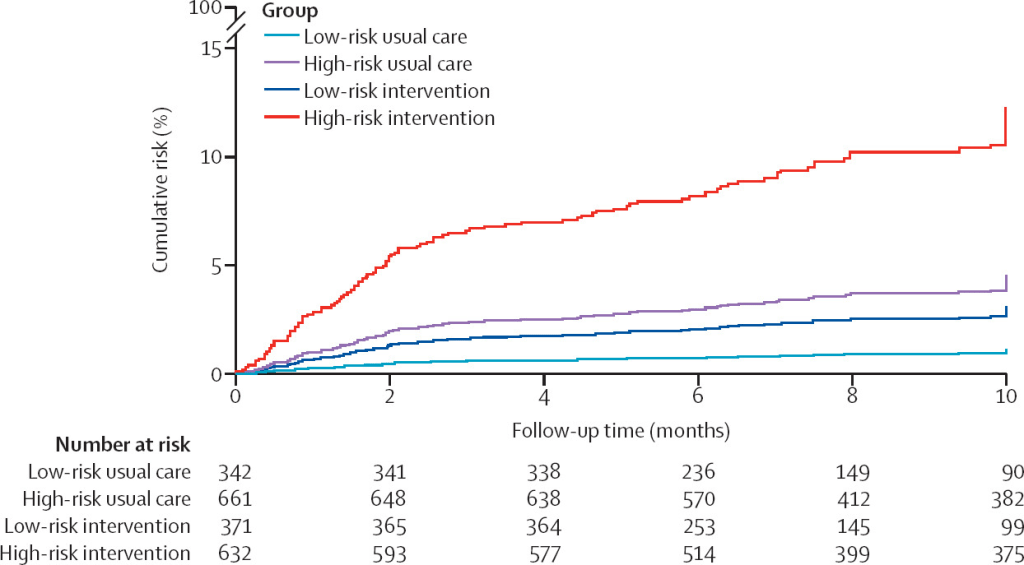

Based on these criteria, the Mayo Clinic identified >650,000 patients who received an ECG in the stated time period. 15,165 met full screening criteria and were invited to participate with 1,003 completing the full monitoring for inclusion in the results analysis. These patients were compared to a propensity matched control group that did not participate in the screening. Patients came from across the US, had an average age of 74 years and average CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3.6. After monitoring for a mean of 22 days, 54 total patients met the primary outcome. Of these, 1.6% were from the AI labeled low risk group and 7.6% form the high risk group (odds ratio 5.0, 95% CI 2.1–11.8, P<0·05). These findings were similar across AF threshold. Interestingly, adding other other AF risk scores on top of the AI ECG did not help improve diagnostic yield, and importantly, using these risk scores alone (i.e. CHARGE-AF) to stratify patients into high and low risk groups did not lead to well differentiated diagnostic yields (4.0% vs 6.0% in low vs high risk, respectively). When compared to a control group of propensity matched patients not included in the screening, there were more AF diagnoses in both low and high risk groups (see image below), and this was statistically significant in the high risk cohort (HR 2.9, 95% CI: 1.8-4.4, P<0.05). Among patients diagnosed with AF during this monitoring period, 76% were initiated on anticoagulation based on these results.

Summary

In summary, a reproducible AI algorithm has been developed which can readily identify patients at high risk for paroxysmal AF, and many of those patients may be unaware of this risk. Importantly, this algorithm is based solely on the evaluation of the patient’s ECG, which is an extremely common and low-cost diagnostic tool used frequently in everyday practice. There is currently no consensus for or against screening at-risk individuals and the USPSTF concluded that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms for screening (i.e. preventing morbidity and mortality balanced against cost to the health system and individual as well as anxiety associated with false positives). Good screening tools are easy to administer, inexpensive, cause minimal harm/discomfort, and are reliable and valid in their ability to discriminate against patients with and without the disease. We know that continuous monitoring identifies patients with AF, but we have yet to identify a select group of patients for whom continuous monitoring would be beneficial. Based on the evidence presented, AI enabled ECGs have a lot of promise for this specific purpose. With further testing they may even be able to identify patients at high enough risk that initiation of anticoagulation would be beneficial during the monitoring period. Hopefully these tools will be readily integrated into the clinical workflow, either by incorporation into the ECG collection software or via the EHR backend. Unfortunately, implementing these promising tools tends to take time in the healthcare setting. It is encouraging that this work is ongoing; stay tuned!

Please subscribe to our Newsletter for email notifications containing new posts as soon as they are published: