As a physician with a deep interest in implementing technological advancements to improve healthcare delivery and physician satisfaction, I’ve followed the progression of medical artificial intelligence (AI) with cautious optimism. The recent unveiling of Microsoft’s MAI-DxO (Medical AI Diagnostic Orchestrator) and its companion benchmark, SD Bench (Sequential Diagnosis Benchmark), represents a notable leap forward—both in technological sophistication and in how we evaluate clinical reasoning in AI systems.

But as with all paradigm shifts, it is worth examining not only what this system promises, but also what it omits, where it may mislead, and how it fits into the broader evolution of diagnostic medicine. Overall, I was very impressed with the research findings, but the caveats and limitations are just as important to emphasize.

What Is MAI-DxO and SD Bench?

SD Bench introduces a more realistic way of assessing diagnostic tools. It transforms 304 stepwise clinical cases from the New England Journal of Medicine’s (NEJM) Clinicopathological Conference (CPC) series into interactive challenges. Rather than revealing all patient data at once—as is typical in vignettes or multiple-choice formats—cases unfold sequentially. Clinicians or AI agents must decide what question to ask or test to order next, with each action incurring a simulated cost. This structure mimics the real-world clinical process, where incomplete data, cost concerns, and diagnostic uncertainty shape decisions at every step.

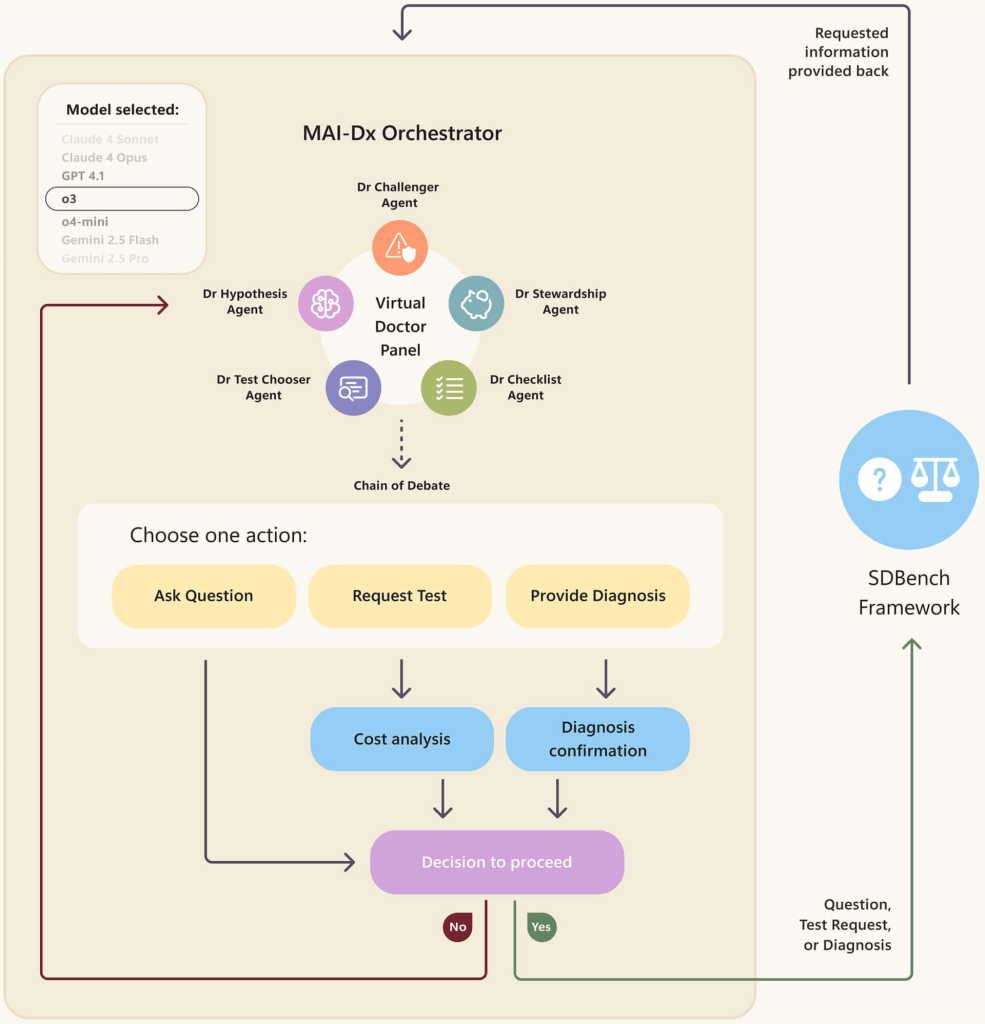

MAI-DxO is an orchestration framework meant leverage this new benchmark. It’s not a single large language model (LLM) with inherent medical knowledge, but rather a “model-agnostic orchestrator.” Think of it as a virtual panel of physicians, each an AI agent with a specific role:

- A Hypothesis Agent maintains the differential diagnosis,

- A Chooser Agent selects the most informative next steps,

- A Steward Agent monitors costs and test burden,

- A Challenger Agent introduces counterarguments,

- A Checklist Agent enforces procedural and clinical safeguards.

MAI-DxO then interfaces with various frontier LLMs (including OpenAI’s GPT, Google’s Gemini, Meta’s Llama, Anthropic’s Claude, and xAI’s Grok), guiding them through this structured “chain-of-debate” framework. Together, these agents simulate the kind of multi-perspective dialogue that defines real-world medical decision-making.

How This Differs from Previous Medical AI and Benchmarking

The key differentiator here is the shift from single-model performance to orchestrated reasoning and the introduction of a more realistic diagnostic benchmark.

Historically, many medical AI benchmarks have been based on medical testing frameworks, like the USMLE (U.S. Medical Licensing Examination). They rely on static formats—either multiple-choice questions or single-pass vignettes. These formats reward factual knowledge and recall but do not capture the iterative, contextual nature of clinical reasoning. We have discussed this benchmarking in previous posts reviewing Google’s medical AI breakthroughs with models like Med-PaLM 2 and Med-PaLM M. SD Bench, with its sequential, cost-aware questioning, attempts to rectify this by simulating real-world diagnostic workflows.

Furthermore, while previous medical AI often focused on training a single, massive model on vast datasets, MAI-DxO’s strength lies in its orchestration method. By combining and coordinating multiple LLMs and guiding them through a structured thought process, it aims to achieve a level of diagnostic precision and cost-efficiency that individual models or unassisted human doctors often struggle to reach, particularly in complex cases.

The Power and Promise of MAI-DxO

The diagnostic accuracy of MAI-DxO on SD Bench reached 85.5%, significantly higher than the 20% accuracy recorded among a cohort of experienced physicians facing the same cases. Importantly, this boost was achieved without additional training or tuning of the base models. MAI-DxO simply directed existing LLMs through a more rigorous reasoning process—and that structure alone enhanced performance.

This is a critical shift. It suggests that clinical performance is not solely a function of knowledge embedded in a single model, but also of how reasoning is architected, evaluated, and constrained.

The system was also remarkably cost-efficient. While achieving higher accuracy, MAI-DxO ordered fewer and more targeted tests compared to both individual LLMs and human clinicians. Simulated cost analyses showed that it reduced diagnostic expenses by over 70% compared to unstructured AI usage and by 20% relative to human physicians.

Perhaps most importantly, MAI-DxO begins to reflect how physicians actually work in practice. ?Clinical teams—especially in interconnected or academic settings—generate hypotheses, challenge each other’s assumptions, choose investigations carefully, and revisit differentials iteratively. MAI-DxO mimics that structured dialogue, bringing a layer of cognitive diversity and internal accountability that static AI models lack.

Caveats and Limitations

Despite its impressive performance, MAI-DxO raises several concerns that merit critical attention.

CPC Case Selection: The “Zebra Problem” in Reverse

The biggest limitation is that the use of NEJM CPC cases introduces a structural bias. These cases are intentionally selected for their rarity, complexity, or educational value. They represent “zebras”—conditions most physicians rarely encounter and favor deep chain-of-thought LLM reasoning.

In contrast, medical training emphasizes the principle: “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” In primary care and emergency medicine, the diagnostic challenge is often distinguishing between common, overlapping conditions—not solving a mystery illness. Human clinicians in real-world settings use pattern recognition and heuristics to triage common cases quickly.

By training and testing MAI-DxO on a dataset composed entirely of rare or atypical presentations, the system may become over-attuned to complexity, increasing the risk of over-testing in everyday scenarios. Ironically, this may lead to higher costs and unnecessary investigations when the system is exposed to more typical clinical workflows.

This highlights a fundamental tension: while CPC cases are excellent stress tests for reasoning, they do not reflect the diagnostic landscape that most clinicians operate within.

Comparison to Human Performance May Be Misleading

The physicians evaluated on SD Bench were restricted from using external resources—no textbooks, online reference tools, or peer consultation. This does not reflect modern medical practice, where access to knowledge is ubiquitous and diagnostic work is often collaborative. It is in fact the opposite of what MAI-DxO was built to reflect.

In contrast, MAI-DxO simulated a multi-specialist panel and had full access to LLMs trained on broad medical literature. The asymmetry in these conditions raises questions about the validity of the reported performance gap.

Risk of Data Leakage

While Microsoft states that SD Bench cases were drawn from recent NEJM publications and filtered to prevent memorization, full transparency into LLM training corpora is still lacking. Publicly available CPC cases or discussions could have influenced the base models indirectly.

Without independent auditing or open training documentation, it remains difficult to completely rule out data leakage, which could inflate reported performance.

No Real-World Clinical Deployment—Yet

MAI-DxO has not been tested in live clinical workflows. It remains a proof-of-concept operating in a simulated environment. Real-world medicine introduces additional layers of complexity: incomplete information, emotional nuance, evolving symptoms, and the essential human aspects of patient interaction and shared decision-making.

Moreover, questions around accountability, safety, and regulatory oversight remain open. If MAI-DxO contributes to a diagnostic error, where does the responsibility fall?

A Diagnostic Assistant, Not a Replacement

Despite these limitations, MAI-DxO’s true value does not lie in competition to clinicians, but in supporting them—especially in the types of cases that elude quick diagnosis.

For common conditions—viral illnesses, hypertension, common dermatologic conditions—the efficiency of experienced clinicians is difficult to surpass. These are the “horses,” and physicians diagnose them quickly with minimal testing. But in cases involving rare diseases, multisystem symptoms, or prolonged diagnostic uncertainty, MAI-DxO could serve as an effective second opinion. This has profound implications for generalist clinicians and hospitalists, especially those practicing in certain settings:

- Rural or underserved regions, where subspecialty access is limited.

- Overburdened health systems, where wait times for referrals are measured in months.

- Telemedicine, where immediate access to multispecialty input is impractical.

In such settings, MAI-DxO could surface rare differentials earlier, recommend high-yield testing, and help avoid diagnostic delay—without requiring full replacement of the physician’s judgment or rapport with the patient.

Conclusion: Toward Process-Based AI in Medicine

With MAI-DxO and SD Bench, Microsoft has introduced not only a new AI tool, but a new AI framework for thinking about diagnosis. This system does not simply recall facts—it reasons, debates, prioritizes, and adapts. In doing so, it brings diagnostic AI one step closer to the collaborative, process-oriented nature of real medical practice.

To fully realize its potential, MAI-DxO must be evaluated in prospective, real-world settings. Its cost savings, reasoning quality, and safety must be validated outside of the controlled conditions of SD Bench to ensure it generalizes to the majority of conditions treated in current healthcare settings. Regulatory frameworks will need to evolve, and clinical workflows will need to adapt.

But the vision is compelling: a future where AI supports, refines, and elevates clinical decision making. Where diagnostic uncertainty is met with intelligent partnership and, where even in the absence of a specialist, the next best thing—structured, data-informed, collaborative reasoning—can be just a click away.

To ensure timely access to posts and future updates, be sure to subscribe to This week in Cardiovascular AI – an email newsletter for followers and subscribers that summarizes recent research in Cardiovascular AI.